The DMCBH celebrates the International Day of Women and Girls in Science by highlighting the diverse career paths of women in STEM.

What sparked your love for science? A childhood curiosity, a great teacher, or a moment of discovery? On February 11, we celebrate the stories of women who turned their passion into a career, inspiring the next generation to do the same. Learn more about the stories of these DMCBH faculty and staff:

Dr. Amani Hariri

Assistant Professor, Department of Chemistry, Faculty of Science, UBC

Dr. Hariri began her scientific training as a chemist, studying how small molecules self-assemble and investigating the fundamental building blocks of matter. Her interest in neuroscience took shape during graduate school after a pivotal conversation with her supervisor, Dr. Tom Soh, and neuroscientist Dr. Rob Malenka.

Dr. Hariri began her scientific training as a chemist, studying how small molecules self-assemble and investigating the fundamental building blocks of matter. Her interest in neuroscience took shape during graduate school after a pivotal conversation with her supervisor, Dr. Tom Soh, and neuroscientist Dr. Rob Malenka.

“I wanted to apply a ‘seeing is believing’ mindset to unknown, complex biological questions,” she says. During their collaboration, she became fascinated by both the brain’s amazing intricacy and how much still remains unknown.

Personal experiences with friends and family affected by mental health challenges further shaped her research focus. Recognizing that many current treatments rely on trial and error rather than precision, she became motivated to develop better tools. Inspired by pioneers such as Dr. Karl Deisseroth and Dr. Zhenan Bao, her work now centers on decoding the brain’s chemical language to enable more precise approaches to brain disorders.

As a first-generation university graduate, Dr. Hariri initially found scientific role models in books and stories. She was especially inspired by figures like Marie Curie, whose persistence in the face of barriers encouraged her to pursue her ambitions, even when she encountered few female faculty role models early in her career.

During graduate school, mentorship from Drs. Gonzalo Cosa and Hanadi Sleiman helped shape her development as a scientist. A gifted copy of The Dark Lady of DNA, a biography of Rosalind Franklin, resonated with her own work studying DNA nanostructures. Watching Dr. Sleiman, who came from a similar cultural background and held herself to exceptionally high standards, showed her what was possible.

What she enjoys most about her work is the forward-looking nature of neuroscience and the collaborative, curiosity-driven environments she has experienced throughout her career.

“The inherent curiosity to solve complex problems, unknown ones, is what drove me to this type of work,” she says. “I dislike the predictable; for me, the excitement lies in the challenge of thinking multi-dimensionally to find the right answer or hypothesis in a sea of data.”

For women and girls in science, Dr. Hariri offers this advice:

“Stay curious, keep your mind open to new opportunities, and do not let your immediate environment limit what you really want to pursue. While having role models directly around you certainly makes the path easier, you can nowadays try to find them in the ‘cloud’, in stories and shared knowledge. One mentor is rarely enough, so surround yourself with many; they can often enlighten you on strengths you possess that you did not see in yourself.”

Dr. Annie Ciernia

Assistant Professor, Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Faculty of Medicine, UBC

Dr. Ciernia’s love for science began when she was a little girl, tagging along with her dad to the greenhouse where he worked as a research technician in plant sciences.

Dr. Ciernia’s love for science began when she was a little girl, tagging along with her dad to the greenhouse where he worked as a research technician in plant sciences.

“Over the holiday breaks, he cared for students’ experiments, and I would “help” by watering plants and pulling weeds,” Dr. Ciernia recalls fondly. “I’m sure I unintentionally sabotaged more than a few graduate projects, but those visits sparked a genuine curiosity about how living things work.”

As an undergraduate research assistant in a cognitive neuroscience lab, Dr. Ciernia became fascinated by the challenge of understanding the brain—how it processes information, shapes behaviour, and ultimately makes us who we are.

She credits her undergraduate supervisor, Dr. Chris Friesen, as a particularly influential mentor. “Working directly with her shaped the core of my scientific training and showed me the kind of mentor I aspire to be.”

Today, mentoring trainees in her own lab is Dr. Ciernia’s favourite part of the job. “Watching them grow into thoughtful, creative scientists—each with their own strengths and perspectives—is incredibly rewarding and energizing,” she says.

For young women in science, Dr. Ciernia offers this advice:

“Stick with it. If you discover an area of STEM that excites you, hold onto that passion. Surround yourself with good mentors and supportive peers—they make all the difference when things get challenging, as they inevitably do. Science needs your ideas, your curiosity, and your unique perspective, so stay persistent and trust that you belong here.”

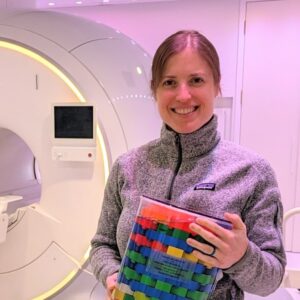

Dr. Erin MacMillan

Philips MR Clinical Scientist, UBC MRI Research Centre

Dr. MacMillan studied biophysics at UBC, where she met Dr. Alex MacKay, who led a lab focused on improving magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain.

Dr. MacMillan studied biophysics at UBC, where she met Dr. Alex MacKay, who led a lab focused on improving magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain.

“As soon as I heard that you could take pictures of the inside of the brain using magnetic fields and radiowaves, I knew that medical physics was for me,” she says.

Shortly after joining the MacKay lab, she was introduced to magnetic resonance spectroscopy, the only non-invasive technique capable of sampling tissue chemistry anywhere in the body. Unlike traditional MRI, which captures structural images, magnetic resonance spectroscopy can detect biochemical changes caused by disease or improvements following therapy.

“It is very exciting to find out what is happening at the biochemical level inside the brain of people actually living with the disease,” she says.

Dr. MacMillan feels fortunate to have had many role models and mentors throughout her career, including Drs. MacKay, Piotr Kozlowski, Irene Vavasour, Corree Laule, Shannon Kolind, Carolyn Sparrey and Rebecca Feldman, and Ms. Laura Barlow.

Today, she loves working with her team at the UBC MRI Research Centre and collaborating on research across a wide range of diseases. She also appreciates that magnetic resonance spectroscopy measurements take only a few minutes, often allowing her to see results almost immediately.

When asked what advice she would give to young women in science, Dr. MacMillan emphasizes the value of hands-on experience:

“My biggest advice is to do co-op and an honours thesis in your undergrad degree. Both of these opportunities offered me the chance to learn what I like and what I didn’t like in research (turns out I’m not very good at cardiac MRI!). During my co-op and honours thesis projects I had the chance to travel to different research groups and build a network of colleagues that I still connect with today!”