Brain Canada recently chatted with Dr. Shannon Kolind about the various ways she’s working to improve brain health.

Dr. Shannon Kolind is a rising star in medical physics at UBC and an expert on a technology referred to as low field, portable MRI. If you’ve ever had an MRI before this term might sound like a misnomer. These MRI scanners use a very low magnetic field – almost 25 times weaker than the magnets in clinical MRI scanners, basically only slightly stronger than a fridge magnet – and are roughly 1/5th of the cost. Thanks to advances in magnetic coil technology and imaging algorithms, they’re small enough to fit through a doorway and use less power than a cappuccino maker. They are also easy-to-use and can be operated by non-experts; in other words, no highly trained MRI technologist on hand? No problem – specialized training is not required to operate the scanner.

And as Dr. Kolind explains, low field MRI scanners are still able to produce excellent, clinically useful images. The accessibility of this technology – both throughout a hospital and in remote areas – is potentially game-changing for a healthcare system needing to cut costs while also boosting quality of care and saving lives.

“The portable scanner is meant to act as a quick and low-cost screening tool, complementary to regular MRIs,” Dr. Kolind says. “It democratizes access to care, helping to even the playing field so that more people can get scanned – and get proper diagnosis and treatment.”

Dr. Kolind and her team were one of the first in Canada to receive one of these scanners and they are working to optimize it for various purposes. Simply put, they’re developing instructions they transmit to the device to help it detect certain brain features. As a 2020 Future Leader in Canadian Brain Research, Dr. Kolind’s Brain Canada-funded work is focused on developing protocols to detect and monitor the progression of lesions in the brain that are the signature of Multiple Sclerosis (MS). With her funding from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation as part of the UNITY (Ultra-Low field Neuroimaging In The Young) project, Dr. Kolind and her team are also developing protocols to study the effect of malnutrition on brain development and evaluate the efficacy of interventions in low- and middle-income countries. When asked if these projects are connected, Dr. Kolind nods profusely.

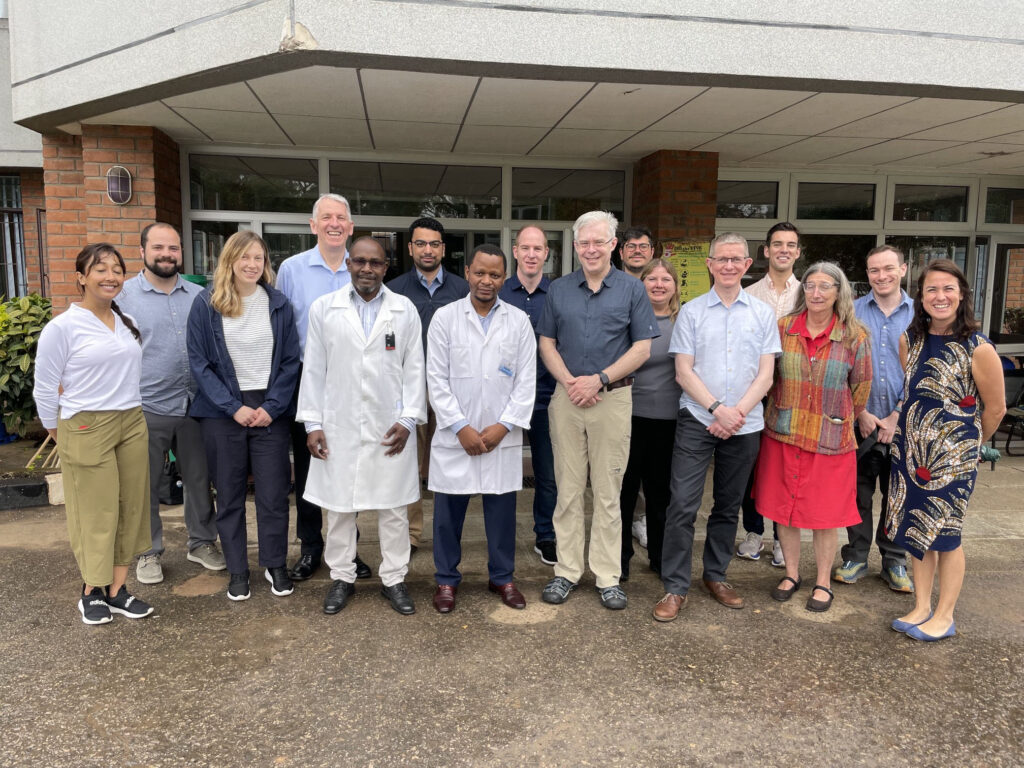

Researchers and clinicians from Blantyre Malawi, one of the pioneering sites operating a Hyperfine scanner as part of the UNITY project, with visiting researchers from UBC and King’s College London, and representatives from Hyperfine, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, and the International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine.

“Absolutely. The outcomes are different but the protocols that we’re developing and the learnings for the MS-focused work will apply to the UNITY project and vice versa,” she explains. “The major difference is that hospitals in countries such as Malawi, Kenya, and Uganda are outside, which can make it challenging to transport the scanner to where it needs to be.”

Dr. Kolind has a strong team working alongside her to address these challenges, including PhD student Adam Dvorak, who traveled with her to sub-Saharan Africa, and industrial collaborators at Hyperfine, the U.S.-based company responsible for manufacturing and continuously improving the scanner. Dr. Megan Poorman, Hyperfine Inc.’s Clinical Scientist and biomedical engineer, explained that it’s a mutually beneficial relationship. The company provides Dr. Kolind and her team with research tools, and in turn Dr. Kolind provides Hyperfine Inc. with data from their scans so that the company can improve its software.

Dr. Kolind’s various energetic graduate students bring expertise in physics, neuroscience, neurology, and computer science to the team. One of Dr. Kolind’s graduate students, Neale Wiley is a fully trained and certified MRI technologist who knows all the ins and outs of scanning from a healthcare perspective.

“My Future Leader grant gave me a huge boost in productivity,” Dr. Kolind explains. “It allowed me to hire the people I needed to develop my research program and move it forward.”

Since she was awarded the grant in 2021, Dr. Kolind has:

- Received additional funding to build on her work, including a $90,000 grant from Michael Smith Health Research BC to support post-doctoral fellow Dr. Hanwen (Kevin) Liu in exploring machine learning approaches with the scanner.

- Hired 10 team members (e.g., graduate students, research assistants and technicians) to work on this project, three of whom are supported through her Future Leader grant funds.

- Made 19 presentations, more than 40% of which were delivered by trainees and several of which required travel enabled by the grant.

- Established a dozen new collaborations, including a new international working group she co-developed that brings experts on low field MRI together, within the North American Imaging in MS Cooperative (NAIMS). Dr. Kolind has also established collaborations with groups studying mood disorders, stroke, malaria, encephalopathy, Alzheimer’s disease, motor neuron disease and more. She hopes to extend her research to include a vast range of neurological injuries and conditions.

- Taken on the co-lead role for the imaging working group of CanProCo, a Brain Canada-funded platform focused on enhancing data collection for MS and improving our understanding of the factors involved in disease progression. The platform has enrolled close to 950 people living with MS across five Canadian MS clinics. Analyses are underway to thoroughly characterize the cohort and prepare for longitudinal analyses that will take place as more participants attend follow-up visits.

- Developed a series of surveys for various stakeholders, including caregivers and clinicians, which will be distributed to solicit input on using low field MRI for MS.

“It’s still early days in terms of bringing this to bedside and rolling it out in remote communities, but that’s our goal. We’re testing our protocols and getting results, and there’s a lot of interest in what we’re doing; I’ve had conversations with several health authorities about using these scanners in practice,” says Dr. Kolind.

Vancouver General Hospital, for example, recently purchased a portable scanner to test its use in the intensive care unit. These scanners are particularly useful for people who are claustrophobic; because only their heads need to be placed in the scanner, and the low field enables a faster scan, so it’s a more comfortable experience. Dr. Kolind has been helping to train staff on the technology and determining best use in this setting.

Dr. Kolind was also asked what motivates her.

“I’ve actually never taken a biology course,” she reflects. “I wasn’t interested in medicine. It’s too squishy! But when my grandmother was diagnosed with dementia, the opportunity to apply my training in physics to imaging to be able to see what was going on in her brain, was game-changing.”

Dr. Kolind and her research team, including Neale Wiley (right), a fully trained and certified MRI technologist.

“In the case of MS, most people don’t get diagnosed until they’re late stage. Low field MRI promises to make early detection easier. It will also make it easier to track the progression of the disease. It’s really rewarding to work on a technology that could make such a significant difference in people’s lives.”

Dr. Shannon Kolind is an Associate Professor and Associate Head (Research) in the Division of Neurology, Department of Medicine at the University of British Columbia (UBC), a member of the Djavad Mowafaghian Centre for Brain Health and ICORD, and an MRI Physicist with UBC MRI Research.

A version of this story was originally published on the Brain Canada website.