Researchers have discovered evidence of brain shrinkage and cognitive decline among individuals with mostly mild SARS-CoV-2 virus infection. Published in the journal Nature in March 2022, the first longitudinal imaging study of its kind compares the brain scans of people taken before and after the start of the global COVID-19 pandemic.

“Study participants who had a positive COVID-19 test showed greater loss of grey matter as well as greater abnormalities in brain tissue, mostly found in the olfactory area related to the sense of smell,” says co-author Dr. Soojin Lee, who is a postdoctoral fellow at the Pacific Parkinson’s Research Institute which is led by DMCBH member Dr. Martin McKeown. “The scans also showed greater global changes, such as overall shrinkage of the brain, in individuals who had contracted COVID-19. All of these changes in the brain were greater among older infected participants.”

Dr. Soojin Lee.

The research team drew their data from a UK Biobank database. Brain scans from the same 785 UK Biobank participants, aged 51 to 81, were taken before and after the start of the pandemic, on average three years apart. Among them, 401 tested positive for COVID-19 between the two scans — based on medical records or two rapid antibody tests — and 384 did not contract the virus.

The COVID-19 infected participants were diagnosed between March 2020 and April 2021, and most of them were infected between October 2020 and January 2021. “This means that a small minority of the participants were likely infected with the original strain, and a majority with an Alpha, Beta or Gamma variant of the virus,” says Lee.

The COVID-19 infected group and non-infected group were similar in terms of age, sex, socio-economic status and risk factors such as high blood pressure, diabetes and smoking.

Measurable brain changes linked to loss of smell and inflammation

Brain changes observed among infected individuals were in terms of their total brain size and specific regions of the brain — orbitofrontal cortex, parahippocampal gyrus and primary olfactory cortex. These changes are likely associated with loss of smell and/or inflammation.

“On average, infected participants had a 0.2 to two per cent additional loss of brain mass or tissue damage compared to non-infected individuals,” says Lee.

To put this in context, most healthy adults will lose between 0.2 to 0.3 per cent of their grey matter in regions of the brain related to memory per year. However, any additional loss is of concern.

Study participants’ cognition was assessed using the Trail Making Test, which is widely utilized to evaluate cognitive/executive function through a task of connecting a series of numbers (Trail A) or a series of alternating letters and numbers (Trail B).

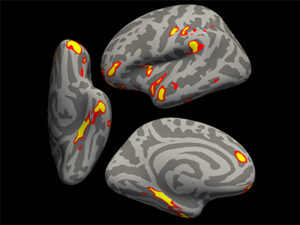

The more substantial red-yellow zones show brain shrinkage in areas related to the sense of smell among SARS-CoV-2 infected participants, as compared with non-infected participants.

Credit: G. Douaud, in collaboration with Anderson Winkler and Saad Jbabdi, University of Oxford and NIH.

Researchers found overall declines in cognitive function among infected individuals, who took on average 7.8 per cent (Trail A) and 12.2 per cent (Trail B) longer to complete the test than their non-infected counterparts. This finding remained significant (6.5 and 12.5 per cent increase in Trails A and B, respectively) even after removing the 15 participants who had severe illness and were hospitalized, and comparing the remaining 386 infected participants to the controls.

The loss of smell experienced by many people who contracted COVID-19 is likely behind some of the observed brain changes, says Lee. The adage “use it or lose it” holds true in this case, as the loss of smell leads to brain atrophy in centres of the brain responsible for this function. Similar results have been found in other research studies of patients who lost their sense of smell, but more studies are needed before a decisive conclusion can be made.

Recovering from these changes may be possible. Prior research found that, when a person’s sense of smell was restored, many of the observed brain abnormalities were reversed.

To this end, researchers aim to continue tracking the recovery of infected participants in follow-up studies. “We are planning several other investigations into the mechanisms behind the disease and the recovery process after infection,” says Lee.

This story was originally published by the Vancouver Coastal Health Research Institute. It can be found here.